Cardiac arrest and heart attack are both life‑threatening heart emergencies, but they are not the same: a heart attack is a “plumbing” problem caused by blocked blood flow to the heart muscle, while cardiac arrest is an “electrical” failure in which the heart suddenly stops pumping effectively. A heart attack can sometimes trigger cardiac arrest, but many cardiac arrests occur without a preceding heart attack, and the urgency, symptoms, treatment, and survival patterns differ markedly between the two conditions.

Cardiac Arrest vs Heart Attack: Understanding the Difference, Saving Lives

What This Article Covers

- What a heart attack (myocardial infarction) is and how it happens

- What sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is and why it is often instantly fatal

- Key symptom differences, risk factors, and emergency responses

- A gender‑ and year‑based case study illustrating real‑world impact

- A 2022–2026 update table summarizing trends, statistics, and innovations in care

Circulation vs Electricity: Core Definitions

What Is a Heart Attack?

A heart attack, medically called myocardial infarction (MI), occurs when blood flow in a coronary artery is blocked or severely reduced, depriving a portion of the heart muscle (myocardium) of oxygen. Most often, this results from rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery, triggering thrombus (clot) formation that obstructs flow. Without rapid reopening of the artery via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or fibrinolytic drugs, the affected myocardium undergoes ischemia and necrosis, permanently weakening the heart’s pumping function.

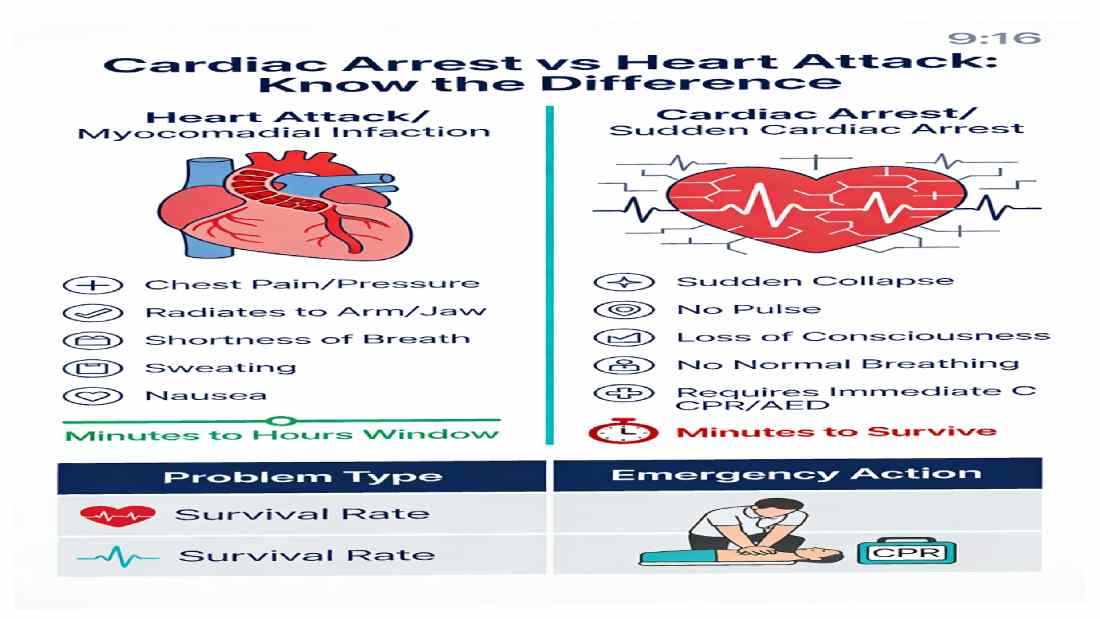

Common features of a heart attack include:

- Chest pain or pressure, often described as squeezing or heaviness, lasting more than a few minutes or coming and going

- Pain that may radiate to the left arm, jaw, neck, back, or upper stomach

- Shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, or vomiting

- In women, more frequent atypical symptoms such as unusual fatigue, lightheadedness, indigestion‑like discomfort, or breathlessness without obvious chest pain

Crucially, the heart usually continues beating during a heart attack, which means patients can remain conscious and have a window of minutes to hours to reach medical care. However, if large areas of myocardium are damaged, electrical instability can develop, precipitating sudden cardiac arrest.

What Is Cardiac Arrest?

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is an emergency in which the heart abruptly stops pumping blood effectively due to a severe electrical disturbance, such as ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. In ventricular fibrillation, the ventricles quiver chaotically instead of contracting, causing immediate loss of cardiac output; within seconds, the person collapses, loses consciousness, and has no detectable pulse.

Key features of cardiac arrest:

- Sudden collapse without warning

- Unresponsiveness to voice or touch

- No normal breathing (may have gasping, agonal breaths)

- No pulse detected in major arteries

Cardiac arrest may arise from:

- Ventricular arrhythmias due to ischemic heart disease or prior MI

- Cardiomyopathies (dilated or hypertrophic)

- Congenital channelopathies (e.g., long QT syndrome)

- Severe heart failure, myocarditis, or structural heart disease

- Trauma, massive hemorrhage, electrolyte imbalance, or drug toxicity

Unlike a heart attack, death occurs within minutes without immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation. Survival is heavily time‑dependent: for each minute without CPR and defibrillation, survival probability decreases by 7–10%.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Feature | Heart Attack (Myocardial Infarction) | Cardiac Arrest (Sudden Cardiac Arrest) |

| Primary problem | Circulation “plumbing”: blocked coronary artery | Electrical “wiring”: chaotic rhythm or asystole |

| Heart activity | Usually continues to beat | Stops or becomes ineffective; no pulse |

| Onset | Often gradual, symptoms over minutes–hours | Abrupt, often without warning; collapse in seconds |

| Consciousness | Often awake; may be distressed but responsive | Rapid loss of consciousness and responsiveness |

| Time window | Hours for treatment (but “time is muscle”) | Minutes; requires immediate CPR/AED |

| Treatment | PCI or fibrinolytics, antiplatelets, anticoagulants, beta‑blockers, ACE‑I, statins | High‑quality CPR + early defibrillation + advanced life support |

| Survival (typical) | Hospital MI mortality 6–9% in many OECD countries | Out‑of‑hospital SCA survival ≈10–18%, depends on rhythm and bystander CPR |

Epidemiology and Survival: 2022–2026 Snapshot

Heart Attack (Acute Myocardial Infarction)

- Coronary heart disease (CHD) caused 371,506 deaths in the U.S. in 2022, remaining a major driver of mortality despite decades of progress.

- Approximately every 40 seconds, someone in the U.S. experiences a myocardial infarction.

- Average age at first heart attack: 65.6 years for men and 72.0 years for women.

- OECD data show in‑hospital MI mortality has declined to around 6.5–8.9% in many countries by 2023, reflecting improved acute reperfusion and secondary prevention.

Sudden Cardiac Arrest

- U.S. data for 2022 show 19,171 deaths where sudden cardiac arrest was the underlying cause, and ≈418,000 deaths where SCA was mentioned anywhere on the death certificate—highlighting SCA’s enormous impact.

- A major 25‑year U.S. analysis found age‑adjusted mortality rates from SCA declined from 196 per 100,000 in 1999 to ≈132 per 100,000 in 2023, with the most pronounced decline after 2021.

- Despite improvements, out‑of‑hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) survival remains low: around 10–18% overall, with 42–48% survival for shockable rhythms and 6–10% for non‑shockable rhythms.

Case Study by Year and Gender: Interplay of Heart Attack and Cardiac Arrest

Male, 58 Years: Heart Attack Without Cardiac Arrest (2022–2024)

Background (2022)

A 58‑year‑old male executive, long‑time smoker with untreated hypertension and elevated LDL cholesterol, experiences intermittent chest tightness during exertion but ignores symptoms.

Event (Late 2023)

He develops severe chest pressure radiating to the left arm and jaw, accompanied by sweating and shortness of breath while climbing stairs. His family calls emergency services within 10 minutes. ECG in the ambulance shows ST‑segment elevation in inferior leads, diagnostic of STEMI.

Management

He receives aspirin and nitrates en route, followed by emergency PCI within 90 minutes of symptom onset, reopening a totally occluded right coronary artery. He starts lifelong dual antiplatelet therapy, beta‑blocker, ACE inhibitor, and high‑intensity statin with structured cardiac rehabilitation.

Outcome (2024)

Left ventricular ejection fraction stabilizes at 50% (mild impairment). He quits smoking, improves diet, and begins regular exercise. No cardiac arrest occurs. His risk of future SCA is reduced through aggressive risk‑factor control and guideline‑directed medical therapy.

Female, 62 Years: Silent Heart Disease Progressing to Sudden Cardiac Arrest (2023–2026)

Background (2023)

A 62‑year‑old woman with type 2 diabetes and obesity has no prior diagnosed coronary artery disease. She occasionally notes unusual fatigue and shortness of breath but attributes it to aging and work stress.

Warning Phase (2024)

She experiences intermittent chest discomfort and indigestion‑like symptoms, which go uninvestigated—an example of atypical female MI presentation.

Cardiac Arrest Event (Early 2025)

While at home, she suddenly collapses and becomes unresponsive. Family members find her pulseless and not breathing normally. Emergency medical services (EMS) are called immediately. Guided by the dispatcher, her spouse performs bystander CPR within 2 minutes.

When EMS arrives, her initial rhythm is ventricular fibrillation, a shockable arrhythmia, and she receives an automated external defibrillator (AED) shock within 8 minutes of collapse. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved; she is transported for targeted temperature management and coronary angiography, which reveals severe multivessel coronary disease and evidence of prior silent MI.

Outcome (2026)

After intensive rehabilitation, she regains good neurological function and receives an implantable cardioverter‑defibrillator (ICD) for secondary prevention. This case highlights that:

- Women may have unrecognized ischemia before SCA

- Immediate CPR and early defibrillation can convert a near‑certain death into survival

- Underlying structural and ischemic heart disease often drives SCA risk

2022–2026 Updates: Incidence, Survival, and Innovation

| Year | Heart Attack (MI) Highlights | Cardiac Arrest Highlights | Key Innovations & Market Trends |

| 2022 | CHD causes 371,506 deaths in the U.S.; MI occurs roughly every 40 seconds. | Underlying‑cause SCA deaths: 19,171; any‑mention SCA deaths: 417,957 in the U.S. | Defibrillator and cardiovascular device markets continue steady growth driven by CVD burden. |

| 2023 | OECD AMI in‑hospital mortality averages 6.7–8.9%; further decline from previous decade. | OHCA survival ≈17–19%; survival with good neurological status ≈15% overall. | Expanded public access AED programs; telecommunicator‑assisted CPR widely adopted, improving bystander response. |

| 2024 | Global CVD deaths ≈19.4 million; heart attacks remain leading cause of cardiovascular death despite declining mortality rates. | Research emphasizes persistent low OHCA survival (≈10%) and need for better risk prediction. | AED market at ≈USD 1.3–1.4B with projected CAGR ~4.7%; devices gain real‑time CPR feedback to improve lay rescuer performance. |

| 2025 | Major analyses show nearly 90% decline in heart attack mortality since 1970 in the U.S., reflecting stents, statins, and public health measures. | 25‑year SCA mortality analysis shows age‑adjusted mortality falling from 196 to ≈132 per 100,000 by 2023, with steeper decline after 2021; mortality remains higher in men. | Cardiac arrest treatment market valued around USD 5B with projected CAGR 4.5%; cardiovascular drug market ≈USD 156B with ongoing growth. |

| 2026 (Projected) | Continued refinement of AMI pathways, AI‑assisted ECG interpretation, and wider statin/SGLT2 use expected to further reduce MI mortality. | New risk‑stratification tools and potential cell‑based therapies under development to prevent arrhythmic SCA, moving beyond pure “rescue” to prevention. | Defibrillator and cardiac rescue device markets forecast robust growth, with increased deployment of wearable and implantable monitoring and therapy devices. |

Practical Takeaways for Readers

Recognize the Symptoms Quickly

- Persistent chest discomfort, especially with radiation and sweating, should be treated as a heart attack emergency—call emergency services immediately.

- Sudden collapse with absence of normal breathing and pulse is cardiac arrest—start CPR and use an AED if available.

Know the Link

- A heart attack can trigger cardiac arrest, particularly when large areas of myocardium are involved or when scarring and electrical instability are present.

- Preventing and treating coronary artery disease reduces both MI and SCA risk.

Prevention Is Powerful

- Control blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, and avoid tobacco to reduce both heart attack and SCA risk.

- Regular health checks and evidence‑based medications (statins, ACE‑I, beta‑blockers where indicated) dramatically lower MI incidence and fatality.

CPR and AEDs Save Lives

- Immediate bystander CPR can double or triple survival from cardiac arrest; combining CPR with early AED shock offers the best chance of neurologically intact survival.

- Learning CPR and advocating for AED placement in workplaces, schools, and public spaces are high‑impact community actions.

Conclusion

Cardiac arrest and heart attack are often conflated, but understanding their distinct mechanisms, warning signs, and emergency responses can be the difference between life and death. Heart attacks are primarily plumbing failures—blocked arteries starving myocardium of oxygen—while cardiac arrest is an electrical collapse that halts circulation within seconds. Heart attacks are more common and often survivable with timely reperfusion, whereas cardiac arrest carries far higher immediate mortality and demands instant CPR and defibrillation.

From 2022 to 2026, global data show encouraging declines in both MI and SCA mortality, driven by better prevention, acute reperfusion therapies, wider AED deployment, and stronger resuscitation systems; yet cardiovascular disease remains the world’s leading killer. For readers of thewellhealthorganic.com, the message is clear: know the difference between cardiac arrest and heart attack, act fast in emergencies, and invest in long‑term prevention through lifestyle, regular check‑ups, and adherence to evidence‑based therapies. These combined strategies not only save lives in the moment but also contribute to the broader global decline in deadly heart events.